Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

britannica.com

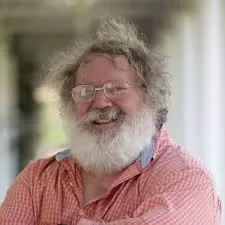

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Birthday:

05 Jan, 1938

Date of Death:

28 May, 2025

Cause of death:

Prostate Cancer & Kidney Disease

Nationality:

Kenyan

Famous As:

Academic

Age at the time of death:

87

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o's Quote's

Early Life: Stories by Lantern Light

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is not just a writer—he is a literary insurgent, a cultural warrior whose pen helped reclaim the dignity of African identity in a world fractured by colonialism. With prose as sharp as it is poetic, he has spent over half a century challenging imperial ideologies, advocating for indigenous languages, and reimagining what literature can do for the oppressed. In every syllable he writes, Ngũgĩ is asking a nation—and a continent—to remember itself.

Ngũgĩ was born James Ngugi on January 5, 1938, in Kamiriithu, a rural village in colonial Kenya. He was the fifth child of his father's third wife, growing up in a sprawling, polygamous household. His early life was shaped by the rhythm of Gĩkũyũ storytelling, oral traditions whispered by firelight, and the haunting tensions of British colonial rule.

During the brutal Mau Mau Uprising, Ngũgĩ witnessed firsthand the violence that tore through his homeland and family. His older brother joined the resistance. Another relative was killed. His own mother was tortured by colonial police. These were not abstract political events—they were personal wounds, ones that would later bleed into his fiction.

Trivia: As a boy, he read discarded newspapers and old missionary texts, teaching himself English before he ever saw a classroom textbook.

Education: The Word as Weapon

Ngũgĩ's brilliance earned him a place at Alliance High School, one of Kenya’s most prestigious institutions, and later at Makerere University in Uganda. There, he published his first major play, The Black Hermit, and began wrestling with themes that would define his life: cultural identity, language, and resistance.

He later completed graduate studies at the University of Leeds in the UK, where exposure to Marxist thought and postcolonial theory gave his work sharper ideological focus. But it wasn’t academic theory that moved him—it was the lived reality of oppression, and the radical possibility of literature as defiance.

While at Makerere, Ngũgĩ published his first novel, Weep Not, Child (1964)—the first major novel in English by an East African. It was an instant classic.

Career Journey: From Novelist to Dissident

Phase 1: Early Novels and National Acclaim

Ngũgĩ’s early novels—Weep Not, Child, The River Between, and A Grain of Wheat—cemented his reputation as one of Africa’s brightest literary talents. Written in English, these books explored colonial violence, cultural conflict, and the complexities of post-independence Kenya.

His writing was praised for its lyricism and moral force. But Ngũgĩ was restless. As he gained prominence, he began to question the very language in which he wrote. Why, he asked, should Africans be forced to express themselves in the language of their colonizers?

Phase 2: Radicalization and Repression

In the 1970s, Ngũgĩ made a dramatic shift—both artistically and politically. He renounced writing in English and began writing exclusively in Gĩkũyũ, his mother tongue. His novel Devil on the Cross was famously drafted on prison-issued toilet paper during his detention in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison in 1977. His crime? Co-writing Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”), a politically charged play performed by villagers in Kamiriithu.

The Kenyan government, threatened by the grassroots mobilization his art inspired, imprisoned him without trial. But jail only deepened his resolve. Devil on the Cross became a testament to the power of indigenous language to challenge power and rewrite narratives.

Fun Fact: Ngũgĩ is possibly the only major author to have written a groundbreaking novel on toilet paper while in solitary confinement.

Phase 3: Exile and Global Voice

After his release, persistent threats forced Ngũgĩ into exile. He lived in the UK, and later the United States, where he became a professor at Yale, then New York University, and finally the University of California, Irvine. In exile, his voice only grew louder. He published Decolonising the Mind (1986), a seminal work of literary and cultural criticism that became required reading in postcolonial studies worldwide.

Even in exile, he wrote prolifically—in both Gĩkũyũ and English—releasing memoirs, novels, essays, and plays that grappled with power, memory, language, and justice.

Personal Life: Scholar, Father, Survivor

Beyond the intellectual and political force of his public persona, Ngũgĩ is a deeply spiritual and family-oriented man. He married Njeeri wa Ngũgĩ, a Kenyan feminist and educator, and together they raised children across continents and cultures.

In 2004, during a rare return visit to Kenya after more than two decades in exile, Ngũgĩ and his wife were attacked in their hotel room—an incident many believe was politically motivated. Even then, he refused to be silenced.

Despite the trauma, he remains remarkably open-hearted and humorous. He plays the flute. He tells stories with warmth and laughter. And even now, in his late 80s, he continues to write, mentor, and speak with an urgency that belies his age.

Legacy: The Prophet of Language Liberation

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has redefined what it means to be an African writer. He has turned language into a battlefield, insisting that true liberation cannot exist unless people can dream, resist, and create in their own tongues. Through fiction, theatre, memoir, and essay, he has built a legacy not just as a literary giant—but as a cultural redeemer.

He has been nominated multiple times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, yet his impact goes far beyond accolades. In classrooms, village theatres, and global forums, his ideas continue to provoke, inspire, and ignite.

As long as African voices echo in indigenous languages, Ngũgĩ’s dream lives on.

Name:

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Popular Name:

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

Prostate Cancer & Kidney Disease

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Kamiriithu, Kenya Colony

Place of Death:

Buford, Georgia, U.S.

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Advocate Quiet and mystical, yet very inspiring and tireless idealists. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was a resolute cultural strategist and compassionate advocate whose pioneering work in language and literature reshaped postcolonial identity and equity.

He renounced writing in English in the late 1970s and began writing solely in his native Gikuyu to promote African languages.

His play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want) led to his arrest and imprisonment without trial by the Kenyan government.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o was the first East African to publish a major novel in English, Weep Not, Child, in 1964.

While in prison, he wrote the novel Devil on the Cross on toilet paper, using it as a form of resistance.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has received numerous international awards recognizing his literary excellence and contributions to African literature and decolonization. These include the Nonino International Prize for Literature (2001), the Nicolás Guillén Lifetime Achievement Award (2006), and the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature (2022). He has also been honored with over ten honorary doctorates from universities worldwide for his cultural and academic impact.